How India Replaced Harish Salve With Pak Lawyer And Paid Rs 1400 Crore To Settle The Dabhol Case

In part-1 of #RepublicExposesEnronScandal, it was revealed how, in 2004, the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government hired a Pakistani-origin lawyer, at 300 pounds per hour, to fight the controversial Enron case. He replaced India’s top legal eagle Harish Salve in the case.Confirming to Republic TV that he was indeed replaced, Harish Salve said, “I thought we had a pretty good defence. But again, I am talking about 2002-04. So, I thought it was a pretty good case. But, memory fades and then there was change of lawyer, then I have absolutely no idea of what happened.”

In part-2 of the #RepublicExposesEnronScandal, documents accessed by Republic TV revealed how India paid a staggering amount of Rs 1400 crore in three tranches to settle the case.

Back in 2004, US multinational giants General Electric and Bechtel bought Enron's 65 per cent stake in the controversial Dabhol Power Company. While the cap fixed was at $300 million, the settlement reached was of $305 million dollars. The Indian Government paid Bechtel $160 million and paid GE $145 million. These large sums of payment made by the UPA allowed US companies to become rich at the cost of the Indian farmers.

The farmers, who were promised employment and compensation for losing their land in the Dabhol debacle, are yet to get their due. More than 700 families continue to be affected.

India Had A Decent Chance In Enron Case: Harish Salve

Republic TV's Legal Editor spoke to former Solicitor General of

India Mr. Harish Salve on the Enron Saga, as a part of the channel's

Mega Exclusive investigation into the scandal.

Excerpts from the interview:

RHYTHM: To understand what really happened in the Enron saga, we are speaking to Former Solicitor General of India Mr Harish Salve, who was replaced when India had a good case but threw it all away. Mr. Salve, thank you for joining us. The first thing that I want to ask you is - you were at the helm of affairs when the Dabhol controversy happened. You were the Solicitor General, you were later replaced. Do you remember how the case was? Do you think the Enron case as it was, was a good case for India, sir?

HARISH SALVE: Rhythm, this is quite a while ago. I remember first draw to action on behalf of financial institutions and we had taken the provision that PTA is tainted by fraud.....I don't remember the details why but, I do remember we were at a pretty decent place. We got interim junctions. The matter was carried to the Supreme Court. I think we successfully defended to the court to try and resolve it.. But, at that time all the junctions were in place. The next thing we knew is, to the best of my recollection, that the GE battle took off in action against the insurance companies, in which it was a common premise that the 'PTA is valid but, PTA is not paying'. So they got some [inaudible] in their favour.

The insurance company brought the matter against Government of India and State of Maharashtra. The Government of India was absolutely clear that there was no action and how can you accuse the Government of India without any merit. I thought we had a pretty good defence. But again, I am talking about 2002-04. So, I thought it was a pretty good case. But, memory fades and then there was change of lawyer, then I have absolutely no idea of what happened.

RHYTHM: And Mr. Salve, we also wanted to know about the case, you were dropped and unceremoniously there was a Pakistani Lawyer Khawar Qureshi who was brought in. We have papers that indicate he was paid 200-300 pounds per hour. At a time when there were escalated tensions with Pakistan. Why do you think the Government would do something that is so out of the ordinary — to drop its top most lawyer who is ready to appear for them at a small charge and bring in an internaional lawyer — a Pakistani lawyer who is asking for hiked rate.

HARISH SALVE: Well, I don't know. This is something which you can ask the people who had arrived at that time. I mean a lawyer is the choice of the client. They wanted somebody they got somebody. Why they got, how they got, whom selected, whom is the matter of........I don't honestly know, Rhythm. As far as we were concerned, we were out of it and that was the end of it. By God's kindness I have never had [inaudible] bothered to find out what happened

RHYTHM: How did this entire proceeding happen Mr. Salve? The fact that you were at the helm of affairs and were suddenly told to leave and someone was brought in. Was it a smooth process? Did they ask you for anything? Did you give them any opinion?

HARISH SALVE: No.....no. I remember we were working on something, Shailendra Swarup and I. He told me that they wanted the work in progress and I said look it is not fair to say work in progress to somebody because by definition it is not in progress and who takes the responsibility? I mean this is again you are asking me things which I [inaudible].

RHYTHM: Right. By work in progress Mr. Salve, you mean they wanted some notes which you might have made in the Enron case to be handed over to Qureshi?

HARISH SALVE: Yeah, we were working on it. You know stuff which we have done and [inaudible] work in progress is my tentative work. So, some may say it's my tentative work and the fact that if I can't take responsibility, it is not fair to pass it off. If somebody says it is from Mr. Salve, then I mean I myself can change it completely. So that's it. But, this is again I don't know a long time ago which I don't remember at all. After all.....

RHYTHM: Yes

Excerpts from the interview:

RHYTHM: To understand what really happened in the Enron saga, we are speaking to Former Solicitor General of India Mr Harish Salve, who was replaced when India had a good case but threw it all away. Mr. Salve, thank you for joining us. The first thing that I want to ask you is - you were at the helm of affairs when the Dabhol controversy happened. You were the Solicitor General, you were later replaced. Do you remember how the case was? Do you think the Enron case as it was, was a good case for India, sir?

HARISH SALVE: Rhythm, this is quite a while ago. I remember first draw to action on behalf of financial institutions and we had taken the provision that PTA is tainted by fraud.....I don't remember the details why but, I do remember we were at a pretty decent place. We got interim junctions. The matter was carried to the Supreme Court. I think we successfully defended to the court to try and resolve it.. But, at that time all the junctions were in place. The next thing we knew is, to the best of my recollection, that the GE battle took off in action against the insurance companies, in which it was a common premise that the 'PTA is valid but, PTA is not paying'. So they got some [inaudible] in their favour.

The insurance company brought the matter against Government of India and State of Maharashtra. The Government of India was absolutely clear that there was no action and how can you accuse the Government of India without any merit. I thought we had a pretty good defence. But again, I am talking about 2002-04. So, I thought it was a pretty good case. But, memory fades and then there was change of lawyer, then I have absolutely no idea of what happened.

RHYTHM: And Mr. Salve, we also wanted to know about the case, you were dropped and unceremoniously there was a Pakistani Lawyer Khawar Qureshi who was brought in. We have papers that indicate he was paid 200-300 pounds per hour. At a time when there were escalated tensions with Pakistan. Why do you think the Government would do something that is so out of the ordinary — to drop its top most lawyer who is ready to appear for them at a small charge and bring in an internaional lawyer — a Pakistani lawyer who is asking for hiked rate.

HARISH SALVE: Well, I don't know. This is something which you can ask the people who had arrived at that time. I mean a lawyer is the choice of the client. They wanted somebody they got somebody. Why they got, how they got, whom selected, whom is the matter of........I don't honestly know, Rhythm. As far as we were concerned, we were out of it and that was the end of it. By God's kindness I have never had [inaudible] bothered to find out what happened

RHYTHM: How did this entire proceeding happen Mr. Salve? The fact that you were at the helm of affairs and were suddenly told to leave and someone was brought in. Was it a smooth process? Did they ask you for anything? Did you give them any opinion?

HARISH SALVE: No.....no. I remember we were working on something, Shailendra Swarup and I. He told me that they wanted the work in progress and I said look it is not fair to say work in progress to somebody because by definition it is not in progress and who takes the responsibility? I mean this is again you are asking me things which I [inaudible].

RHYTHM: Right. By work in progress Mr. Salve, you mean they wanted some notes which you might have made in the Enron case to be handed over to Qureshi?

HARISH SALVE: Yeah, we were working on it. You know stuff which we have done and [inaudible] work in progress is my tentative work. So, some may say it's my tentative work and the fact that if I can't take responsibility, it is not fair to pass it off. If somebody says it is from Mr. Salve, then I mean I myself can change it completely. So that's it. But, this is again I don't know a long time ago which I don't remember at all. After all.....

RHYTHM: Yes

Enron in India: The Giant's First Fall

In 1992, the Enron Corp. announced it would build a $3 billion natural-gas power plant in Dabhol in the western state of Maharashtra. The project was to be the poster child of economic liberalization in the country -- the single largest direct foreign investment in India's history.

Instead, Enron in India has been an economic disaster and a human rights nightmare.

From the get-go, the Dabhol project was mired in controversy. Enron worked hand in hand with corrupt Indian politicians and bureaucrats in rushing the project through. Charges filed by an Indian public interest group allege Enron and the Indian company Reliance bribed the Indian petroleum minister in 1992-93 to secure the contract to produce and sell oil and gas from the nearby Panna and Mukta fields to supply the plant.

A Human Rights Watch report recounted incidents of farmers' land stolen, water sources damaged, officials bribed and opponents of the project arrested on trumped-up charges. In 1997, the state police attacked a fishing village where many residents opposed the plant. The pregnant wife of one protest leader was dragged naked from her home and beaten with batons.

The state forces accused of abuses provided security to the Dabhol Power Corporation (DPC), a joint venture of Enron, the Bechtel Corp. and General Electric, overseen by Enron.

The U.S. State Department issued the DPC a human rights clean bill of health. Charged with the assessment was U.S. Ambassador Frank Wisner, who had also helped Enron get a contract to manage a power plant in Subic Bay in the Philippines in 1993. Shortly after leaving his post in India in 1997, Wisner took up an appointment to the board of directors of Enron Oil and Gas, a subsidiary of Enron.

Thanks in part to Wisner's positive rights review, Washington extended some $300 million in loan guarantees to Enron for its investment in Dabhol -- even though the World Bank had refused to finance the project, calling it unviable.

A recent Indian investigative committee report exposed an "utter failure of governance" -- bribery, lack of competitive bidding, secrecy, etc. -- by both the Indian federal government and two successive state governments as they rushed the Enron project through.

By June 2001, the Maharashtra state government had already broken off its agreement with DPC because its power cost too much. That was the plant's one and only customer.

By December, news of Enron's collapse was in newspapers across the world. But the company still filed a $200 million claim with the U.S. government's Overseas Private Investment Corporation, a U.S. taxpayer-funded insurance fund for American companies abroad, in an attempt to recoup losses from the DPC. Indian newspapers reported that Vice President Dick Cheney, Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neil and Commerce Secretary Don Evans tried to twist the Indian government's arm into coughing up the money. Otherwise, U.S. officials warned, other investment projects would be jeopardized. International media reported last month that U.S. government documents showed Cheney tried to help collect the debt.

Today in Dabhol, the power plant is considered polluting and undependable. Spring water has become undrinkable, the mango crop is blighted and the fish catch is dwindling. Often at nightfall, the electricity fails.

How did Enron manage to push the project through? By using a time-tested strategy. Centuries ago, the East India Company went to India to trade and stayed on to rule. Before long, Indian money and goods were feeding coffers in London, and the products were sold back to the colony. The DPC was in India, but the money went to Enron's offshore tax shelters. And just like the East India Company, Enron appeared to apply a strategy of divide and conquer. It offered groups of villagers money, hospitals and lucrative labor contracts, with the result that families sometimes became divided against each other.

Pakistan's lawyer at ICJ once pleaded for India in Enron case: report

ANI

Published May 22, 2017, 12:31 pm IST

Updated May 22, 2017, 12:31 pm IST

Millions of dollars were at stake for India and initially Harish Salve was retained as a counsel, but then replaced by Qureshi.

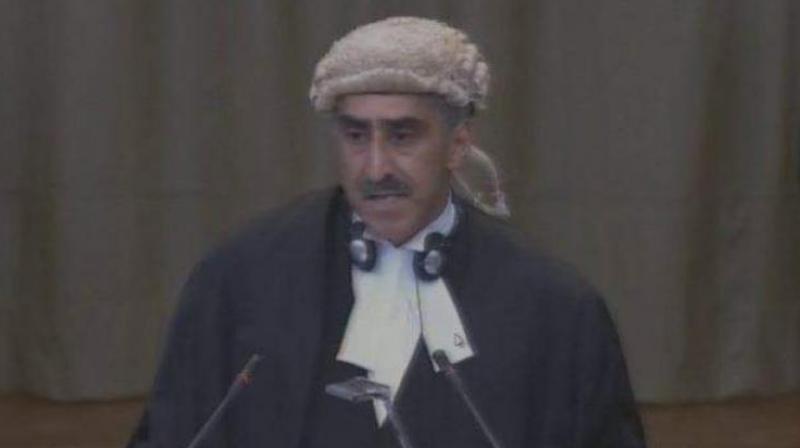

Pakistan lawyer Khawar Qureshi. (Photo: ANI Twitter)

New Delhi: Lawyer Khawar Qureshi who represented

the Pakistan government at the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

hearing on the Kulbhushan Jadhav case, represented India 15 years ago in

an arbitration matter in the United States.

According to the Dawn, the arbitration before an international tribunal in the United States was initiated by Enron over the closure of the Dabhol power project in 2004.

Millions of dollars were at stake for India and initially Harish Salve, who is representing India at ICJ currently, was retained as counsel for a concessional fee of Rs 100,000 for a day's hearing.

However, a sudden change of heart forced the legal firm Fox and Mandal to hire Qureshi.

India ultimately lost the Enron case and also paid a heavy fee to Qureshi.

According to the Dawn, the arbitration before an international tribunal in the United States was initiated by Enron over the closure of the Dabhol power project in 2004.

Millions of dollars were at stake for India and initially Harish Salve, who is representing India at ICJ currently, was retained as counsel for a concessional fee of Rs 100,000 for a day's hearing.

However, a sudden change of heart forced the legal firm Fox and Mandal to hire Qureshi.

India ultimately lost the Enron case and also paid a heavy fee to Qureshi.

The Dabhol Power Company (now called RGPPL - Ratnagiri Gas and Power Private Limited) was a company based in Maharashtra, India, formed in 1992 to manage and operate the controversial Dabhol Power Plant.[1] The Dabhol plant was built through the combined effort of Enron, GE, and Bechtel. GE provided the generating turbines to Dabhol, Bechtel constructed the physical plant, and Enron was charged with managing the project through Enron International. From 1992 to 2001, the construction and operation of the plant was mired in controversies related to corruption in Enron and at the highest political levels in India and the United States (Clinton administration and Bush administration).[2]

In 2001, the power plant ran into trouble due to Enron scandal leading to the bankruptcy of Enron.[3]

In 2005, it was taken over and revived by converting it into the RGPPL (Ratnagiri Gas and Power Private Limited), a company owned by the Government of India.[

The plant was to be constructed in two phases. In March 1995, the ruling Congress Party in Maharashtra lost to a nationalist coalition that had campaigned on an anti-foreign investment platform. In May, hundreds of protesting villagers swarmed over the site to protest the displacement of people that would take place, and a riot broke out. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International eventually charged the security forces guarding Dabhol for Enron with human-rights abuses; Human Rights Watch blamed Enron for being complicit. On August 3, the Maharashtra state government ordered the project to be halted because of "lack of transparency, alleged padded costs, and environmental hazards." Construction ground to a halt. By then, Enron had invested about $300 million into the project.[5]

Phase One

Phase one was set to burn naphtha, a fuel similar to kerosene and gasoline. Phase one would produce 740 megawatts and help stabilize the local transmission grid. The power plant's phase one project was started in 1992 and finally completed two years behind schedule.Phase Two

Phase two would burn liquefied natural gas (LNG). The LNG infrastructure associated with the LNG Terminal at Dabhol was going to cost around $1 billion.[6]In 1996 when India's Congress Party was no longer in power, the Indian government assessed the project as being excessively expensive and refused to pay for the plant and stopped construction. The Maharashtra State Electricity Board (MSEB), the local state run utility, was required by contract to continue to pay Enron plant maintenance charges, even if no power was purchased from the plant. The MSEB determined that it could not afford to purchase the power (at Rs. 8 per unit kWh) charged by Enron. From 1996 until Enron's bankruptcy in 2001 the company tried to revive the project and spark interest in India's need for the power plant without success. The project was widely criticized for excess costs and deemed a white elephant. Socialist groups cited the project as an example of corporate profiteering over public good. Over the next year Enron reviewed its options. On February 23, 1996, the then government of Maharashtra and Enron announced a new agreement. Enron cut the price of the power by over 20 percent, cut total capital costs from $2.8 billion to $2.5 billion, and increased Dabhol's output from 2,015 megawatts to 2,184 megawatts. Both parties committed formally to develop the second phase. The first phase went online May 1999, almost two years behind schedule, and construction was started on phase two. Costs would now ultimately climb to $3 billion. Then everything came to halt. The MSEB refused to pay for all the power, and it became clear that getting the government to honor the guarantees would not be an easy task. Although Maharashtra still suffers from blackouts, it says it does not need and cannot afford Dabhol's power. India's energy sector still loses roughly $5 billion a year. This plant was taken over by Ratnagiri Gas and Power Private limited in July 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment