Scientists Learn How To Make You Forget or Remember While You Sleep

Monday, July 10, 2017 2:49

Scientists at the Center for Cognition and Sociality, within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), enhanced or reduced mouse memorization skills by modulating specific synchronized brain waves during deep sleep. This is the first study to show thatmanipulating sleep spindle oscillations at the right timing affects memory. The full description of the mouse experiments, conducted in collaboration with the University of Tüebingen, is published in the journal Neuron.

The research team concentrated on a non-REM deep sleep phase that generally happens throughout the night, in alternation with the REM phase. It is called slow-wave sleep and it seems to be involved with memory formation, rather than dreaming.

During slow-wave sleep, groups of neurons firing at the same time generate brain waves with triple rhythms: slow oscillations, spindles, and ripples. Slow oscillations originate from neurons in the cerebral cortex. Spindles come from a structure of the brain called thalamic reticular nucleus and spike around 7-15 per second. Finally, ripples are sharp and quick bursts of electrical energy, produced within the hippocampus, a brain component with an important role in spatial memory.

“Often during the night a regular pattern is manifested, where a slow oscillation from the cortex is immediately followed by a thalamic spindle and while this happens, a hippocampal ripple appears in parallel. We believe that the correct timing of these three rhythms acts like a communication channel between different parts of the brains that facilitates memory consolidation,” explains Charles-Francois V. Latchoumane, first co-author of the study.

Figure 1: The triple rhythm of brain waves during non-REM deep sleep

©Freepik.com The electrical fields of groups of neurons in a certain region of the brain give rise to specific patterns of brain waves. Different areas of the brain generate characteristic squiggles of electroencephalogram (EEG) tracings. Peaks (up-states) represent neurons firing at the same time, while minima (down-states) are the sign of neuronal silence. Depending on the origin, frequency and shape, it is possible to distinguish slow oscillations from the cortex, spindles from the thalamus, and ripples from the hippocampus. (credits: modified from Phduet, freepik.com) The researchers focused on spindles because it was shown that the number of spindles is connected with memorization. It has been shown that the number of spindles increases following a day stuffed with learning and declines in the elderly, and in patients with schizophrenia. This is the first study to show that artificial thalamic spindles affect memory, if administered in sync with slow oscillations.

In the experiment, mice were put in a special cage and given a mild electric shock after hearing a tonal noise. The day after, their memory was tested, by checking their fear reaction in response to either the same noise or the same cage. Latchoumane explains that this could be simplified and compared to the experience of hearing a fire alarm in a certain location, like a cafe. The incident would be followed by either another visit to the same cafe or the sound of the fire alarm in another cafe on the following day.

At nighttime between the two days, scientists introduced artificial thalamic spindles in some of the mice using a light-based technique called optogenetics. The mice were divided into three groups. The first group received the light input just after the slow oscillations, so their spindle could form a triple rhythm (in phase): slow oscillation-spindle-ripples. In the second group the light stimulations were applied later “out of sync”. The third group was used as a control and did not receive any light stimulation.

The day after, mice were placed in the same location and their movement was recorded. The mice of the first group were frozen in fear 40% of the time, even in absence of the noise. On the contrary, mice in the second and third groups only froze up to 20%. Instead, when the mice heard the same tone in a different location, remembered the tone and froze in fear up to 40% of the time, independently from the group they belonged to. The hippocampus is involved in spatial memories which might explain the difference

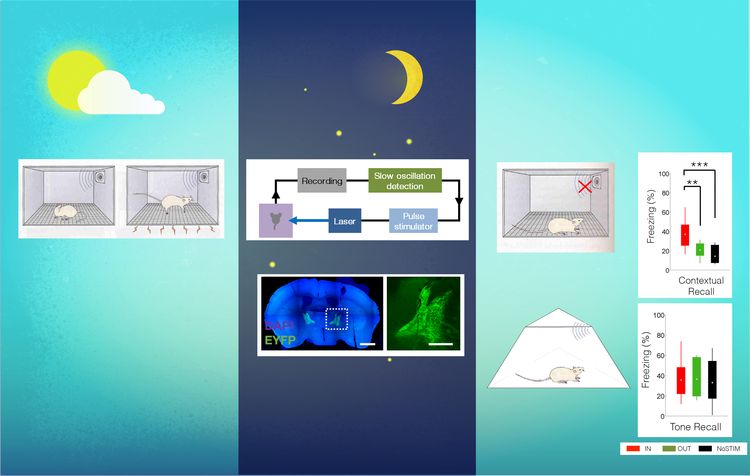

Figure 2: Experimental design to study the effect of artificially induced brain waves.Mice were located in a cage and give a mild electric shock after hearing a noise (left). During the night an optogenetic method (center) was used in some of the mice to induce thalamic spindles artificially. The mice were divided into three groups: in the first group the spindle could form a triple rhythm (IN, red), in the second group the spindle was induced “out of sync” (OUT, green) and in the third group no stimulation was received (NoSTIM, black).

▲ (credits: modified from freepik.com)

The day after, the researchers checked if the mice remembered either the location or the noise (right). If the mice recall the incident, they freeze in fear. If the thalamic spindles were induced in phase with the slow oscillations (IN, red), then the mice were better at remembering the location. If the same noise was presented in a different location, all mice were equally good at remembering it.

Video 1: Artificially introduced thalamic spindles improve mice memory, if properly synchronized with the rhythm of other brain waves.The first mouse is a control which did not undergo any stimulation of thalamic spindles overnight. The second mouse had thalamic spindles induced in phase with the slow oscillations. It does not move so much around the cage (freezing, fear response), as it was better able to recall the incident which happened in the same location the day before

Credit: IBS YouTube channel. (background image modified from freepik.com)

The opposite was also true: it was possible to make mice forget. By reducing the number of overnight spindles, the researchers could reduce the memory recall.

The research team thinks that the thalamus is the coordinator of long-term memory consolidation, the process where recently acquired information is transferred from the hippocampus to the cortex to be filed away as long-term memory. The hippocampus is like a hub, where a lot of information comes in and has to be redirected to the correct destination within the brain, especially to the cortex. This study shows that the thalamus seems to mediate the information exchange between hippocampus and cortex. “We think that memorization during deep sleep has to do with time coordination. If the hippocampus tries to exchange information when the cortex neurons are not ready to receive it, the information could be wasted,” describes Latchoumane. “Slow oscillations might be the signal used by the cortex to flag that it is ready to accept information. Then, the thalamus would alert the hippocampus via the spindles.”

It is possible to foresee that patients with memory deficiencies could benefit from translation of this research into humans. However, several points need to be clarified: can we manipulate single memories independently? Is the REM phase influencing the outcome? How is stored memory retrieved? While waiting for the next research outcomes on the science of sleep, sweet dreams… and sweet memories too.

Contacts and sources:

Mr. Shi Bo Shim

Institute for Basic Science

Citation: Charles-Francois V. Latchoumane, Hong-Viet V. Ngo, Jan Born, and Hee-Sup Shin. Thalamic Spindles promote memory formation during Sleep through Triple Phase-Locking of Cortical, Thalamic and Hippocampal rhythms. Neuron, July 6, 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.025

No comments:

Post a Comment